Portrait and events photographer Nadya Kwandibens uses her lens to tell vibrant and contemporary stories of Indigenous Peoples

In 2000, Nadya Kwandibens enrolled in a film production program at Confederation College in Thunder Bay, Ont. Photography was a compulsory course. While Kwandibens decided not to finish the program, she unknowingly kick-started something more than just a new hobby. In photography, she found a passion that would spark a new purpose.

Kwandibens was working for CBC Radio and studying English literature when she moved to Arizona in 2005. Photography was still something she did just in her spare time. It became serious when, a year later, she started booking portrait sessions. As word spread, her calendar filled. She’s worked non-stop ever since.

Kwandibens is Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) from the Animakee Wa Zhing #37 First Nation in northwestern Ontario. She has spent more than a decade touring Canada and the United States documenting and sharing positive contemporary portraits of Indigenous people and communities. “Many people think there’s this whole team, but it’s just me travelling and building an archive,” says Kwandibens, now a Toronto-based portrait and events photographer. “My work is deeply connected to Indigenous people and who we are. That’s always been the main goal behind my work: to have my photography be an accurate representation and depiction of who we are as Indigenous Peoples – as Nations across Turtle Island – to eradicate negative stereotypes by highlighting our complexities, our realities and our resistance to ongoing colonialism.”

For two years – her starving artist years, she says – she struggled. “Getting through the winter months was always hard, but I knew I couldn’t give up. I believe in my work; it’s taken on a life and spirit of its own,” she says. “And so it’s my responsibility as an artist to honour and take care of that spirit, to carry our stories and create space for a different narrative.”

She started Red Works Photography in 2008 to provide more positive imagery. “At the time, whenever you saw Indigenous Peoples in mainstream media, the images were always that of struggle, strife and stereotypes. Red Works aims to combat that portrayal and says, no, that’s not actually what Indigenous realities look like.”

She named her company Red Works to honour both her culture and her hard work. There’s a concept in some Indigenous cultures called the Medicine Wheel. There are four coloured quadrants; red represents Indigenous Peoples. ‘Works’ speaks to not only the idea of artistic work but also the straightforward concept of the word. “I’ve worked hard to get my photography out there, to share my vision,” says Kwandibens. “Having toured for years, I’ve been doing the groundwork for a long time.”

A series of stories

That same year she launched the first of three ongoing series that challenge perceptions of Indigenous Peoples. Concrete Indians focuses on expressions of contemporary Indigenous identity and decolonization. Kwandibens photographs her portrait subjects, often dressed in full or partial traditional regalia, in urban settings. Like all of her series, it’s open call.

Many participants eagerly reached out from the beginning, sharing not only their life stories but also how they felt about who they are. “To spend time with people, to care for and learn more about people and their lives is the basis of my artistic practice,” she says. “That’s why I say there’s a huge responsibility that comes with holding these stories and portraits. One hundred years from now what will people look back on? Being true to the people is important to me. It’s something I don’t take lightly. ”

One photo from that series now hangs at the west entrance of the library building at Ryerson University in Toronto. The black-and-white portrait is of Tee Lyn Duke, a member of an Anishinaabe dance troupe. Duke, in full jingle-dress regalia, stands in a major subway station interchange during rush hour as a flurry of her fellow commuters hurry home. The installation will be on display for five years.

“The main thing I hope [people take away] is they see that Indigenous people are beautiful; our cultures are vibrant and thriving; and we are persisting and resisting,” says Kwandibens. “I hope people see that’s there’s definitely an Indigenous presence in the city and there always has been. We’ve been here since time immemorial.”

Kwandibens created her second series, Red Works Outtakes, to combat the “stoic Indian” stereotype. She wants subjects to leave her sessions in high spirits. Having done improv theatre, she often applies some of the same techniques during her photo shoots. “The Outtakes are fun! It feels good to push aside those stereotypical images, in particular the work of Edward S. Curtis,” she says. “Humour plays a vital role in our lives. We like to laugh. It’s not always so serious.”

Lastly, The Red Chair Sessions is about language revitalization and Indigenous land. Portrait subjects scout their own location. What ties the series together is they all pose sitting in or standing beside a red chair. “It’s about recognizing that we’re all guests on Indigenous land,” says Kwandibens. “We are visitors to different Indigenous Nations and treaty areas. The red chair represents our bloodlines and our connection to the land and where we come from.”

Her own best teacher

Kwandibens is a self-taught photographer. Recently she’s turned to teaching herself video production and editing as well. So far she’s done two projects, both triptych installations for group exhibitions. She completed RE:Turning Home for Testify, a collective focused on Indigenous laws and governance. Her installation explores the treatment of Indigenous children within the general welfare/foster care system. “This project was crucial and quite emotional for me because I went through the system myself,” she says. “My installation sought to visually convey what that felt like, and to emphasize the significant role that Indigenous cultures have on the development and empowerment of our youth.”

Her second video was part of a 2019 cultural revitalization project called “NISK and stories from the land.” Kwandibens travelled to northern Quebec and documented unscripted conversations between Indigenous youth and elders.

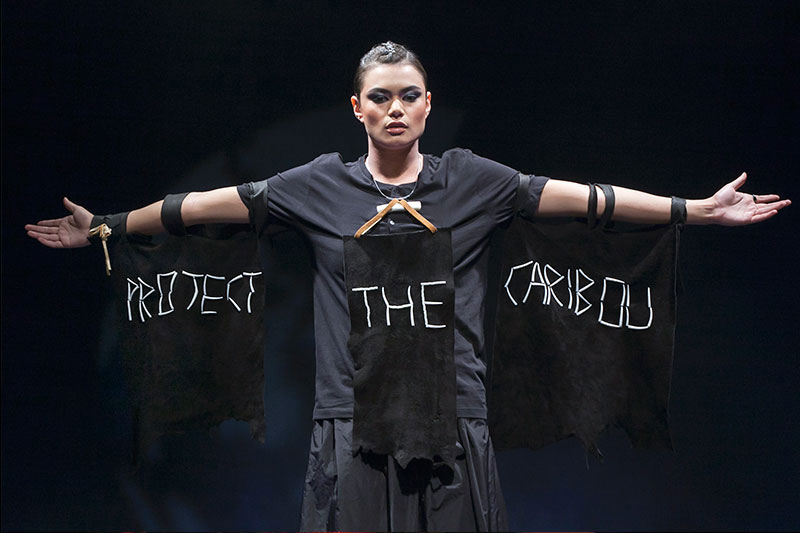

Designer: Tania Larsson | Model: Cleo Keahna | Toronto | June 2018

Giving a voice

Kwandibens provides space and trust for people to tell their stories. She’s excited that over the past decade more photographers are sharing imagery of different Indigenous communities. She’s seen a shift in people’s perceptions of Indigenous Peoples. “I see the changes,” she says. “Changes are happening slowly but need to happen much faster. Indigenous cosmologies, our worldviews and philosophies have much to offer current and future generations. As an artist, to be a part of the continuation of that process is really meaningful.”

In 2019, Kwandibens worked on an education and awareness campaign as part of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). She travelled across the country gathering images of family members who have lost a sister, mother, daughter, aunt, cousin or friend. Kwandibens was careful to create a gentle space for people to tell their stories. She admits, though, the campaign took a toll on her emotionally. “It was a lot to carry. I couldn’t move from bed for a couple of weeks,” she says. “It really speaks to the sheer strength of those who’ve lived with such injustice for so long.”

Kwandibens never likes to end a session with a heavy feeling. Being able to draw some positive energy from such difficult conversations was important. “I always try to help people feel empowered by sharing their stories,” she says. “The entire MMIWG campaign is the most impactful and powerful work I’ve done to date.”

Educating a new audience

The messages Kwandibens aims to address are resonating. “Across my social media profiles, people comment on how much the work means to them and how much a portrait or series has uplifted them and made them feel proud of who they are,” she says.

A few years ago, Kwandibens experienced an influx of new followers to her Instagram account after the social media platform did a feature on her. This broader audience has let her know that they want to learn more.

“Seeing the impact that my photography has had is definitely rewarding,” she says. “Educating people so they may better understand Indigenous reality, our realities, is important. It goes back to understanding my responsibility as an artist. There are so many Indigenous artists working in different streams and mediums who are doing the same work. To be a part of that circle of artists is a great honour.”

Tee Lyn Duke | Toronto | March 2010